From Bars to Books

Photos & Text by Maria Olloqui

“According to the verdict of the jury, it is ordered and adjudged by the Court that you are guilty of murder in the second degree.”

To most, hearing this penalty means spending life behind bars – entering a world of concrete enclosed by a razor wire. To others, it can mean an opportunity to evolve beyond a norm of societal failure.

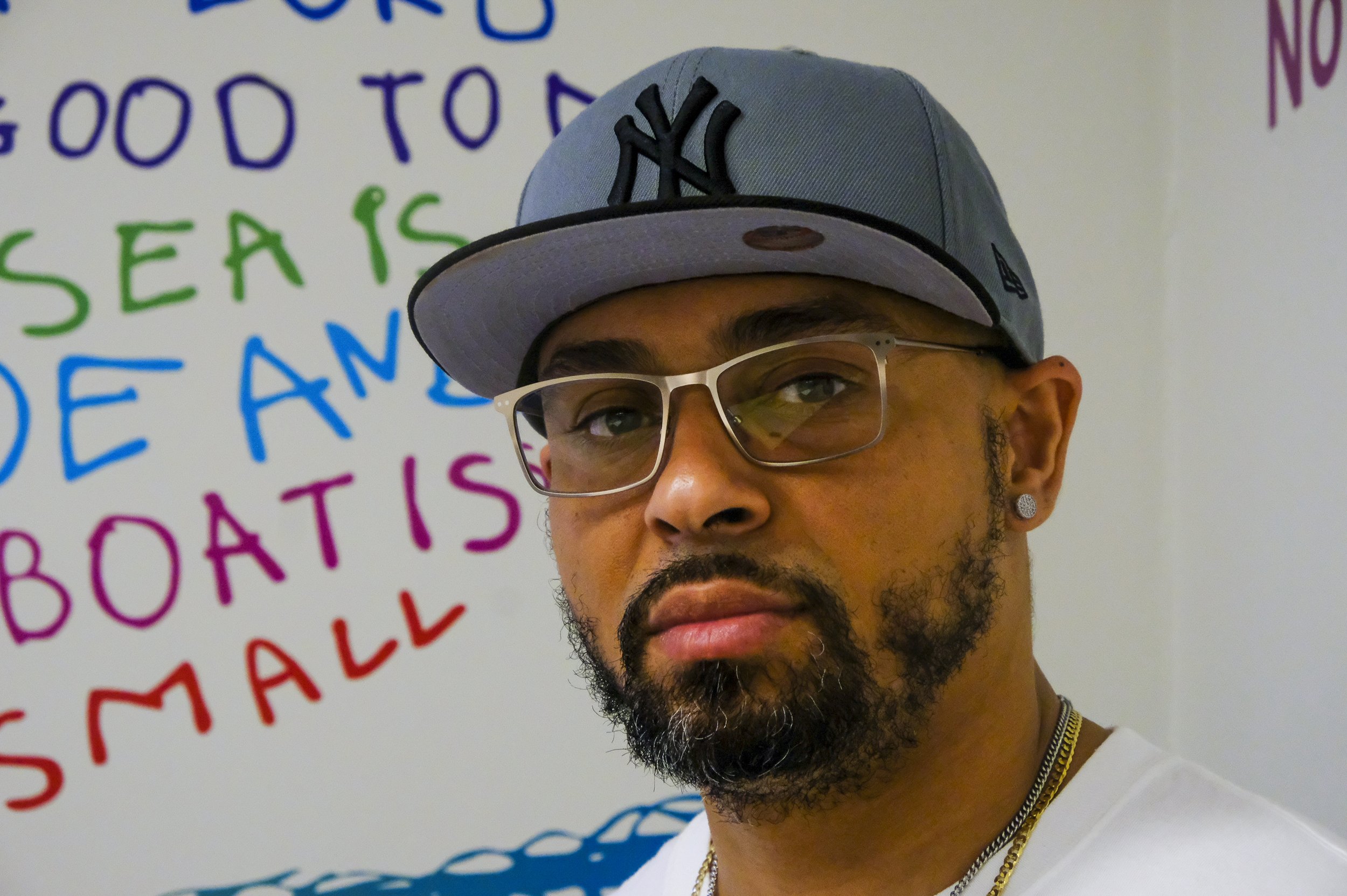

Portrait of Bard Alum Jose Angel Perez. Photo Maria Olloqui.

Jose Angel Perez was 16 years old when he traded his favorite hoodie for a polyester jumpsuit. He was arrested and convicted of murder in the second degree and robbery in the first degree.

Trapped in a mentality of pervasive fear, Perez envisioned himself rotting in prison.

“All I got were 16 years,” said Perez. “And to consider that a life is generous.”

Before getting locked up, Perez was in and out of foster homes for ten years. His mother was in Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, and his father went missing.

While serving time at Downstate Correctional Facility in the Hudson Valley Region, Perez was placed in a strip cell. Naked, accompanied only by a bare mattress and pillow, for surveillance of suicide.

Alone, Perez found an escape – a way to rewrite the few memories he could look back on: poetry.

“It saved me,” said Perez. “Poetry helped me get in touch with humanity.”

Poetry became Perez’s best companion – and also a business. Prisoners would pay him to write poems; in exchange, he got extra money and food.

Today, Perez remains true to his passion. He’s a poet, author, actor, and advocate for child welfare. Perez spends his 9-5 as a project manager at the Children’s Defense Fund, launching a program for foster children transitioning out of care.

"I am blessed to be in a position to engage in the kind of service work that affords me the opportunity to give back to a community I took so much from," said Perez, looking through the glass door of the Children’s Defense Fund office. Photo Maria Olloqui.

“I’m working for my former self and living my dream,” he said.

Perez credits these skills to the Bard Prison Initiative and Sing Sing. It took him four years to be admitted to the coveted BPI program, which was launched by undergraduates at Bard College in 1999 and aims to reduce inequities in higher education across seven prisons in New York State. Sing Sing is the only maximum state prison in the country to offer Master’s degree programs. Alumni become independent tax-paying citizens post-release, armed with degrees and fueled with hope. Virtually none return to their cells.

In January 2023, the largest meta-analysis on the topic of recidivism – or the tendency to re-offend – was launched by the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Findings confirmed that giving prisoners access to education decreases the likelihood of committing another crime by 14.8%. According to The New York Times, race is a weaker predictor of future incarceration than education level. Bard and Sing Sing are proof of that, with less than one percent of graduates re-entering prison.

It is something most know as a remote possibility, with 61% of inmates in the U.S. having less than eight years of education. As of 2018, at least 29 states offer education programs in some of their correctional facilities.

Pre-prison, Perez does not recall touching a book. But, in preparation for BPI admission, he buried himself in his cellmate’s books. He finished White Man’s Justice, Black Man’s Grief cover to cover – and, with it, came a sense of belonging to a community. He read the work of Khalil Gibran and compiled his own set of poetry into three ruled notebooks.

Once accepted to BPI, Perez enrolled in arts and humanities classes. Ultimately, he took leadership development courses at Sing Sing and graduated with a Master’s in Professional Studies.

During his parole board hearing, Perez read the poem he wrote in his strip cell.

“Let me go home,” he said.

"For successful living, only the brave." Jose Angel Perez purchased this necklace after his release from prison. Photo Maria Olloqui.

Bard Alum Patrick Stephens shows off his necklace, gifted to him by his Caribbean community in prison. It represents his favorite reggae group; he refers to it as a token of hope. Photo Maria Olloqui.

May 18, 2022 – the day Patrick Stephens was set free after 24 and a half years.

Portrait of Bard Alum Patrick Stephens. Photo Maria Olloqui.

He was 24 when he got in, following a turbulent childhood during the crack epidemic – an era where cocaine plagued major cities across the U.S.

Stephens dropped out of high school and resorted to drugs; soon after, his parents kicked him out. This led Stephens to D.C., the U.S. murder capital in the 90s.

In 1997, Stephens began to serve time at Eastern Correctional Facility.

“It was hello to this monotonous institution and goodbye to the outside world,” said Stephens.

For the first three years, he had little hope of ever going home. That despair motivated his interest in BPI.

Patrick Stephens stopped by the newly-renovated BPI office to reconnect with other formerly incarcerated people on March 31, 2023. He calls them family. Photo Maria Olloqui.

Stephens was accepted to the program on his first try. Each year, up to 200 prisoners apply to BPI, taking a two-day entry-level exam with excerpt selections in political science, literature, and a topic of social relevance. A group of approximately 40 students are selected for an interview, of which 15 are admitted to begin the following semester.

Higher education behind bars mimics reality. Incarcerated people sit in prison uniforms on classroom desks and embark on coursework matching the caliber of an undergraduate experience. Stephens enrolled in courses including foundations of financial management, counseling, and psychology. It led him to the debate team, which became a significant building block for his current experience in the workplace. But above all, Stephens became inspired by his capstone; he focused on restorative justice, specifically the theological displacement of prisons in the U.S. One aspect of this is making amends to the people that you have harmed – an act that is not permitted in NY state.

Stephens found that the only way to connect offenders and victims is through accountability letter banks. Twelve states run this system of apology, with the victim deciding if, when, and how the letter of remorse is accepted. In the case of acceptance, victims can have the letter mailed or read to them by the Office of Victim Assistance (OVA). While the letter does not grant forgiveness for an incarcerated individual’s sentence, it is a tool to communicate accountability. Stephens hoped to expand upon the acknowledgment of pain by creating a website for victim-offender dialogues in his capstone project.

The idea behind this was more than just a vision. During his time at Fishkill Correctional Facility, Stephens saw the younger brother of the man he killed – a prime witness at his trial with whom he harbored resentment.

“I kept my eyes sealed on him for a week,” said Stephens. “One day, while doing mock parole boards, I couldn’t help but hug him. I said to him ‘Your brother did something that hurt me, and I didn’t know how to handle it.’”

Apology accepted. The act motivated his capstone and the work he does today.

Now, Stephens works at the Center for Community Alternatives, where he is intending to create a restorative justice program – emphasizing trauma and healing. Additionally, Stephens does work with advocacy and organizing in Albany, most recently for clean slate legislation. Simultaneously, he is completing a course about the neuroscience behind trauma.

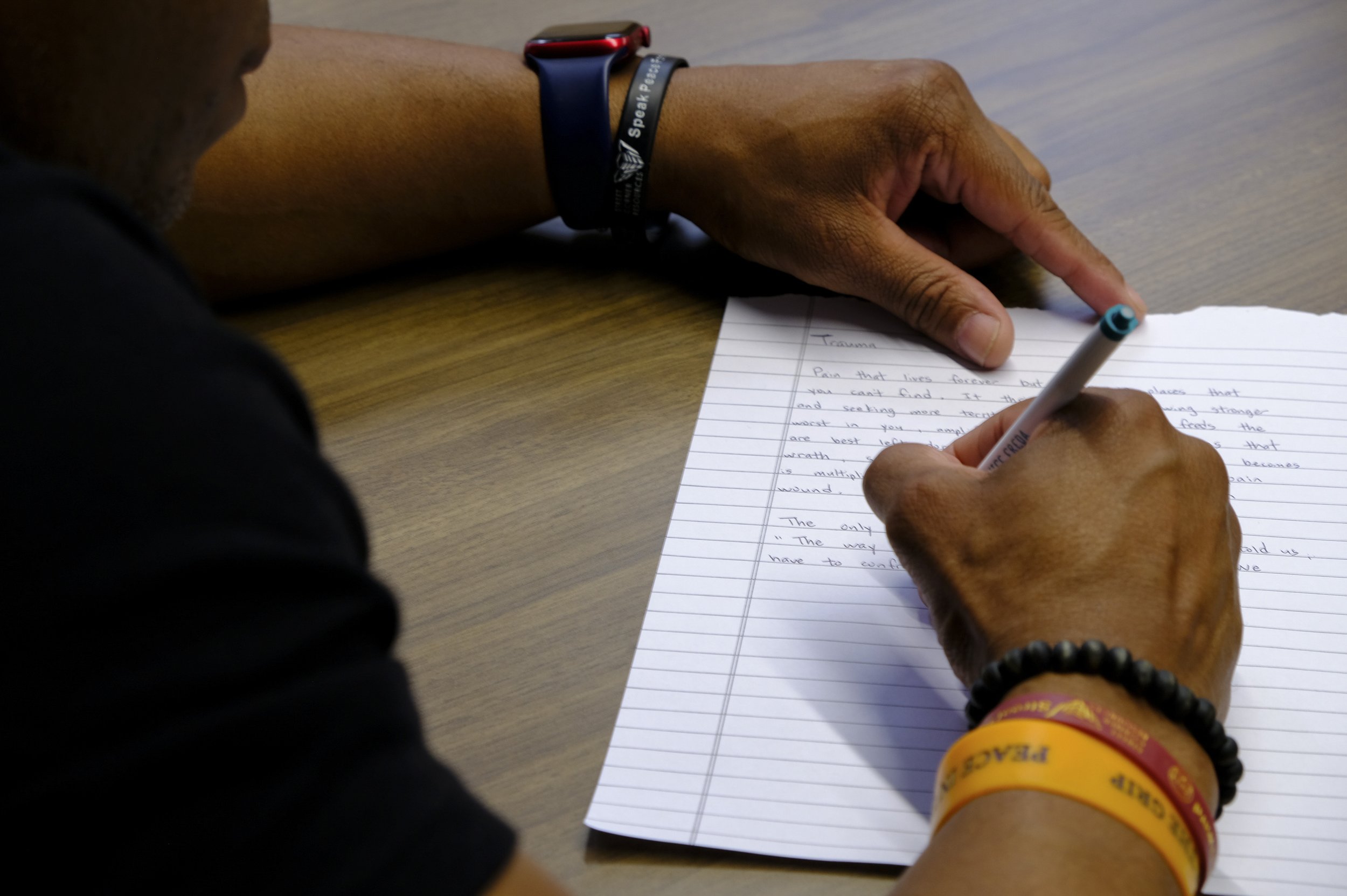

Writing got Stephens through 24 years of prison. He's never put that passion to rest. Here, he writes a free-form piece at the BPI office. Photo Maria Olloqui.

Post-prison, Stephens sees his power in understanding other people's traumas and helping them heal. "Compassion rather than condemnation," he said. Photo Maria Olloqui.

Since graduating, he has also had bylines in The Drift Magazine and The Progressive as a member of Empowerment Avenue’s Writer Cohort. Stephens’ work-in-progress is a piece about incarcerated fathers and COVID-19.

“I couldn’t hug my son the last Father’s Day inside,” said Stephens. “BPI and Sing Sing taught me how to put that into words.”

Stephens credits his education as a vehicle to post-prison success.

“What matters more than the recidivism marker is how formerly incarcerated people impact their communities when they come home,” said Stephens.

“I’m a new person.”

Jose Angel Perez also considers himself a new person since his release. But while he integrates into a new life, his past becomes harder to escape. The mere sight of a guard sends shivers down his spine, triggering memories of the trauma he experienced while incarcerated. The sound of sirens sets off his fight-or-flight response – a vestige of the hyper-vigilance he endured in prison.

For Perez and Stephens, turning the page is like slowly mending a wound. Transforming pain into knowledge, one page at a time.

***

Published Link: https://columbiavisualstorytelling.com/bars-to-books